When you think of the Impressionists, what comes to mind? Maybe you see Monet’s Water Lillies, Degas’ Ballerinas, or Renoir’s rosey cheeked French girls in summer dresses. It is an art movement that is remembered for being pretty, and in truth many of its paintings were pretty. The colors were warm, its feeling was rather upbeat, and its subjects were not very edgy … or were they?

Underneath the pastel colors that the Impressionists are remembered for, was an intense desire to upset the hierarchy that dominated art for nearly five hundred years. They wanted to change the game. They were tired of the conventions of European painting. Like many photographers today, they did not want to be told what they could and could not paint. Earlier efforts of the 17th century Dutch genre painters and the later French Realists like Courbet and Daumier never gained serious momentum. They were always viewed as second tier, in spite of now being regarded as master works. The Impressionists said to hell with all of it; let’s set up our own approach called the Société anonyme des artistes (Society of Independent Artists). It put on exhibitions free from the constraints of the Salon.

Organized annually, the Salon had a governing body of judges. These “art experts” and artists decided what was good art and what was bad art. They were, for the most part, the be all and end all of the art world for over a century. They were ruthless. Their exhibitions were something for which artists would kill themselves or each other in order to be included. But eventually a small group of artists, who would later be known as the Impressionists, started to break away. They were revolting against a few basic ideas that photography now embraces. What were these ideas?

For five hundred years in Europe, there was a hierarchy to paintings. The subject matter determined how important a painting was in the world of art. History paintings and religious paintings sat at the top of the pecking order; this was followed by portraiture, then landscape, and at the bottom were still lives and genre paintings.

You do not need an art history degree to be able to spot them; it is actually quite simple. Here is a quick way to spot each genre.

History Painting: These paintings illustrated major historical events of the distant past. Many of the paintings use allegory. So, for example, if someone was deemed a good ruler, you might find an image of Justice holding her scale. Its roots are in Greek and Roman mythology, and usually looks like a bunch of old people wrapped up in bed sheets. Think Jacques Louis David’s “The Death of Socrates” (pictured above).

Religious Paintings: These paintings illustrated stories from the Bible – Old and New Testament. They were usually commissioned by the Catholic Church, its clergy, or patrons of the Church. The subject matter could vary enormously, they were always linked to characters and stories from biblical history.

Portraiture: These were single, double, or occasionally multiple portraits of living people that the painters usually painted from life. They could be royalty and their families, nobles, merchants, or anyone with enough money to afford it. They used to be VERY expensive, so the guy at the market selling apples was unlikely to have a formal portrait of himself hanging at home. Sitters were often depicted wearing the fashionable clothing of the time.

Landscapes: Paintings of nature did not become really popular until the 1800s. Prior to that, they were seen like backgrounds to other paintings that did not have people in them. Artists were frequently paid for each person they painted in a scene. Which makes the business of painting trees and rocks a low paying gig.

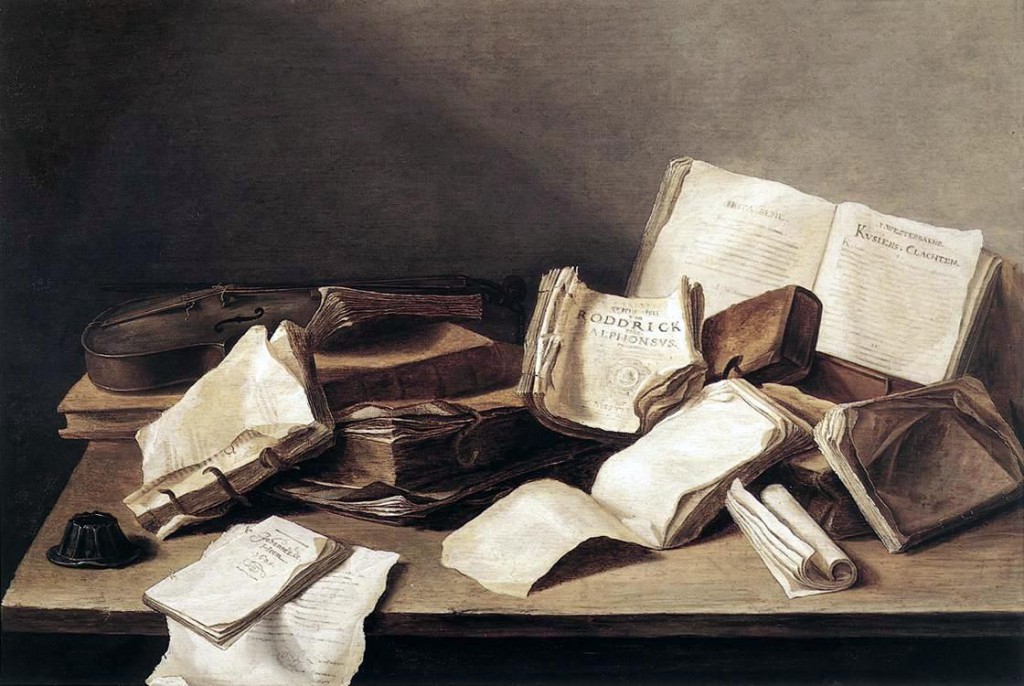

Still Lives and Genre Paintings: At the bottom of the list were still lives and genre paintings. These collections of food, objects, and bric-a-brac worked as great practice for painters, especially in the winter months. Anyone who has been in northern Europe knows that November to April are very much “inside months.” Oil paint gets very stiff in the cold and no one wants to sit for a portrait in the dead of winter. Artists used these paintings for themselves and smaller commissions. But without question, these were not regarded as very significant.

And if the still lives were insignificant, than paintings of people in everyday scenes were even less important. This is actually where many of the original ideas for candid portraiture, street photography, and travel photography find their origins. Sadly for most genre painters, it would take another 300 years before these ideas would really gain traction.

This was the structure that the Impressionists wanted to throw out. They were open about their contempt for this slavish observance of these categories. And can you blame them? They were sick of telling old stories from the past. They were tired of chasing rich clientele for portraits, and half of them were agnostic and could not give a flip about the church. They wanted to paint the world as they saw it.

Now there are some art movements that make manifestos and declare their intentions explicitly. The Impressionists did not do this exactly. However, between their letters and writings, we can get a good sense of their goals and values.

They wanted to paint the world as they saw it.

You might recognize a few of their values from photography. Today I’d like to focus on three characteristics they gave to the world of photography and one that got very mixed up by the world of journalism.

Well before the invention of the camera, the Impressionists gave up on romanticizing the past. They painted plein-aire, or outside and from real life. They walked around with an easel and a paint brush the same way you carry a camera. They were really some of the first artists to take work outside of the studio. This broke down a huge barrier between the general public and the high brow world of art. If you ever feel out of place walking around with a camera, try carrying a wooden box, canvas, and a bag of brushes. The Impressionists made our job as photographers easier for the public to accept.

The Impressionists were sick of telling stories. When people would look at their paintings and ask, “What is the story behind it?” they would answer, “There is no story.” The paintings were about seeing, not telling. This freed them from symbolic figures, religious figures, and afforded them the ability to paint everyday life. They were more interested in capturing a moment in time than a story.

The ironic things is that many of the subjects that the Impressionists painted were enormously influential for early photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, André Kertész, and Werner Bischof, which in turn influenced generations of photographers. But somehow the journalist tendency to tell stories worked its way back into a subject matter that was pioneered because there was no story. Art works in funny ways.

The paintings were about seeing, not telling.

This was an open requirement of the Impressionists: you could not paint like your friend. Degas had to be different from Manet who needed to be different from Pissarro. Even if they painted side by side they had to have a unique touch. Their work needed to be different, in a recognizable way from their friends. Unlike the art of the prior 500 years, which focused on matching an earlier style, they decided that after they were good enough to copy the masters or reach a high level of drawing or painting, they then needed to explore the untouched areas of art.

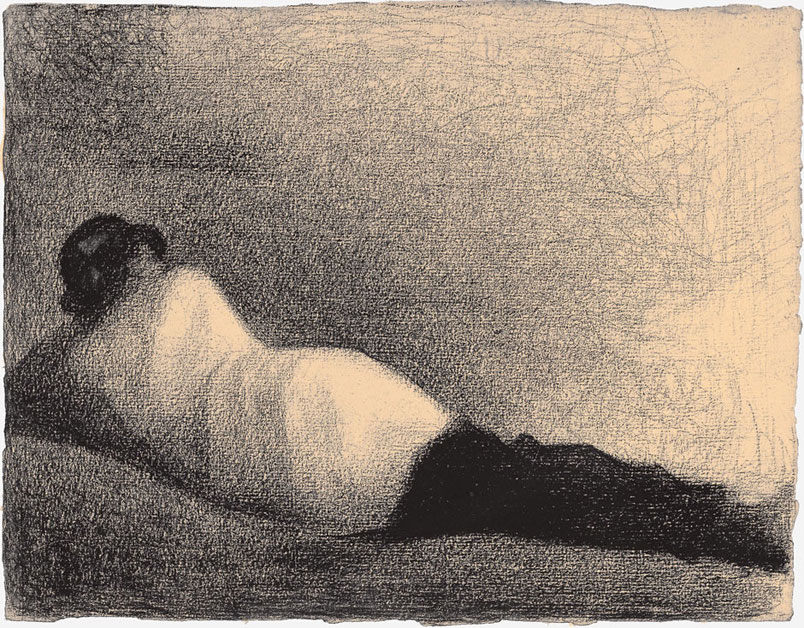

It is worth noting that even the revolutionary Impressionists developed their styles only after they learned the fundamentals. None of them just popped on the scene and started painting whatever they felt like. They trained together, learned under teachers, and succeeded in meeting many of the conventions of design, construction, and perspective before they ventured into uncharted territory. One of the clearest examples of this was George Seurat who, being one of the youngest of the bunch, developed his distinct dark and grainy drawing style. These would go on to be beautiful precursors to night photography and the lustrous qualities of film grain.

What does this all mean for photographers? Well, it puts things in perspective for sure. Think about the problems photographers face…

• Photographers want to show their unique point of view on the world today

• Photographers want to tell a story (a complete inversion of what the Impressionists intended, but now at least you know where it came from)

•. Photographers want to develop their own style

Artistic development is nothing new. People have been wrestling with their creative tendencies for centuries. They have tried to buck the system, invent new ways of seeing, and find fulfillment in their contributions to the art conversation. It is a wonderful and contentious world where the artist resides, but it is good to know that there have been many successful examples before us.

Now I don’t expect everyone to drop their camera and start stocking up on art history books, but a few well chosen examples will carry some useful lessons. It also puts into perspective many of the things that the photo world inherited from the art world. Once you can trace the origin of an artistic activity it will reveal the answers to questions that might have seemed mysterious, but in truth they were hiding in a book and not in a press release for a new camera.